Now is a good time to be an adult gamer, with two fantastic new mature releases in totally different genres. The first and most high-profile, with adverts coating tube stations, is L.A. Noire. Published by Rockstar (of Grand Theft Auto fame) but developed primarily by the Australian Team Bondi, it is nominally an open world game but in reality nothing like previous Rockstar offerings. Instead the narrative-driven game following the rise of straight-as-an-arrow Detective Phelps draws its inspiration from police procedurals and, naturally, film noir’s atmosphere and aesthetics.

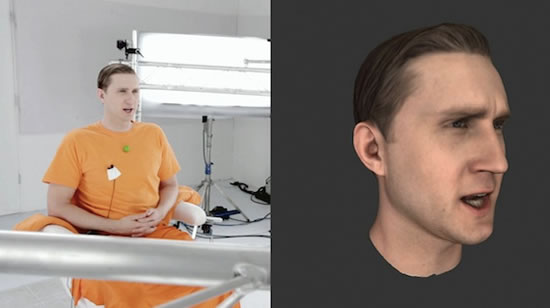

The big draw is the highly impressive MotionScan technology, a substantial leap forward in facial animation, if at times straddling the uncanny valley. Actors’ faces were recorded with an array of 32 cameras so that, when interviewing witnesses, the player must watch for reactions like nervous twitches or shifting eyes to ascertain lies. The fine line between doubting a suspect and confronting them on a lie feels clunky at first but soon becomes natural as you learn how to use the evidence in your notebook. I suspect it was an error instantly to inform the player at the end of an interview how many questions they dealt with “correctly”, since it sparks an intrinsic desire to retry the sequence. Cases are arguably more interesting with an occasionally fumbled interview but ultimately enough evidence to nail the culprit. And earning a five-star rating at the end of an investigation (which doesn’t require 100% success) is always rewarding. However gamers are taught to treat success as being black and white at every stage, and in generally are not wired to accept any level of “failure” as acceptable if the game highlights it as such. While it may be a helpful gauge early in the game, this is a case where providing too much immediate feedback arguably damages the experience.

Indeed L.A. Noire stumbles only when it attempts to fall back on traditional gameplay. The open world approach lets its 1940s Los Angeles feel alive, but the loose GTA-style driving mechanics feel at odds with the the rest of the game, often resulting in unintentional destruction. Similarly the generally violent side-missions are a great diversion but the body-count Phelps builds up seems both unrealistic and out of character (notwithstanding that he is a war veteran), much the same problem that plagues the Uncharted series. The short, disjointed tutorial cases may not give the best first impression but as soon as they open up into full-length investigations, L.A. Noire shines.

The second game, Polish RPG The Witcher 2, deals more overtly with moral ambiguity like its predecessor. Based upon the novels of Andrzej Sapkowski, the world inhabited by supernatural monster-hunter Geralt is a far cry from the typical good versus evil fantasy landscape. Political machinations and racial mistrust underlie much of the experience (more successfully than the other recent fantasy sequel, the rather rushed Dragon Age 2), and even those giving you quests may be lying to you. While Geralt is out to help people, he is also a mercenary with his own code of ethics; this duality between nobility and cynicism has led to comparisons with Raymond Chandler’s private eye Philip Marlow. So despite very different protagonists, these two games are loosely linked by their murky worlds.

Many gamers will find The Witcher 2 hard going, beyond its inexplicable refusal to teach you its own mechanics (without delving into the manual, which feels somewhat archaic these days), because its shades of grey feel inherently unfamiliar. They are too used to simplistic binary moral choices, even from games that boast of more complex morality. Some argue that videogame fantasy is escapism, and so a sharp delineation between “good” and “bad” actions is essential to the player’s enjoyment. Yet such a narrow view is like suggesting all cinema should conform to the simplicity of the summer blockbuster’s “good guys” and “bad guys”. Such escapism is fine, but cinematic gems tend to be rooted precisely in those shades of grey in between. The further games explore such spaces, the more the medium can evolve. And as developers’ skill in crafting such worlds improves, we may find their interactive nature makes videogames better equipped for the job.